- Mon 30 December 2019

- research

- Trevor Metz

- #bicycle, #engineering, #controller implementation, #arduino

This is an updated version of a previous blog post on the implementation of a PID controller on an instrumented ebike which can be found here. Updates include sections 5.4-5.5 discussing the added dead man's switch and throttle relay and minor fixes throughout.

1.0 Introduction

The overall goal of this project is to design and implement a cruise control system for an instrumented ebike used for conducting bicycle handling experiments. A previous blog post (found here) outlines the design and analysis of a continuous time PID controller for controlling the speed of the ebike. This blog post tells the story of how the designed PID controller was implemented digitally on the instrumented ebike through an Arduino Nano and how it fits into the ebike cruise control system that was developed to make functional use of the PID controller.

2.0 System Operation & Functionality

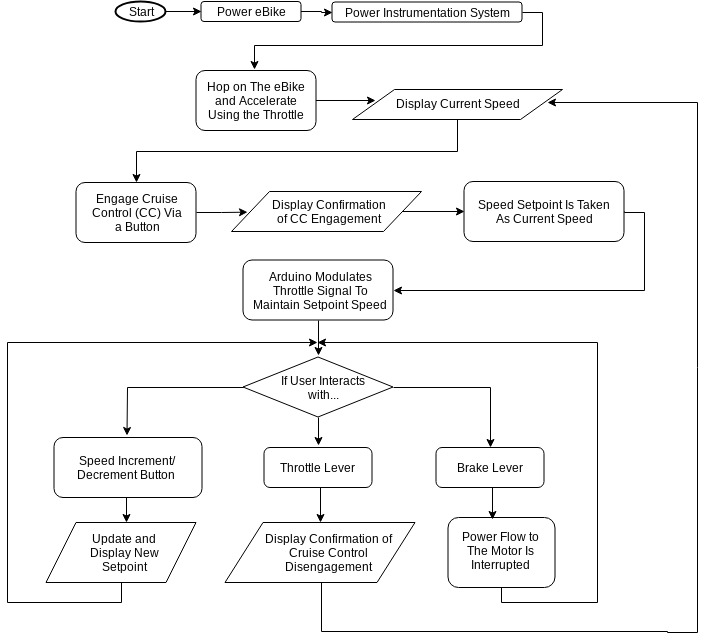

The implementation of the cruise control system on the electric bike was fundamentally informed by the interactions the user would have with the system. A typical user interaction with the system is outlined in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. A typical user interaction with the system.

This user interaction flowchart was used to help better understand the problem of implementing the cruise control system and sculpt the concepts for the hardware and software portions of the cruise control system.

3.0 System Architecture

3.1 Control Architecture

The control architecture is a simple negative feedback design that computes the error between a user defined setpoint and the actual speed of the ebike. Figure 2 graphically shows how the control architecture is implemented on the ebike.

Figure 2. Control architecture as implemented on the ebike.

3.2 Physical Architecture

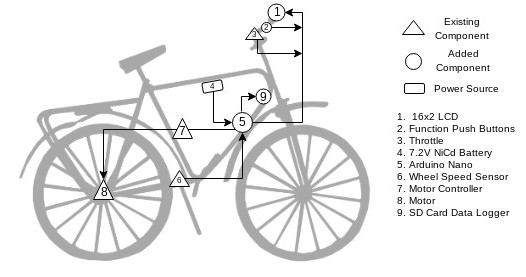

At the heart of the cruise control system’s physical architecture is its integration into the instrumented ebike’s powertrain. Figure 3 shows this integration by highlighting the input/output and geometric relationships between existing components of the ebike and the additional components needed to implement the cruise control system.

Figure 3. Geometric layout of the system components showing relative size, location, information flow, and type of each component. Components called out with a triangle are existing components on the ebike. Components called out with a circle are components that are introduced to the ebike system to implement the cruise control.

The fundamental interaction between the control system and the existing ebike powertrain system occurs at the interface between the Arduino nano and the ebike motor controller. While the cruise control is engaged, the function of the Arduino is to take control of the throttle signal away from the user by passing the calculated output of the control loop to the motor controller instead of the throttle position commanded by the rider. When the cruise control is disengaged, the Arduino simply reads the user commanded throttle position and passes it directly to the motor controller. Figure 4, below, graphically shows this interaction.

Figure 4. Schematic showing the Arduino’s function as a throttle emulator.

Note: Testing of the cruise control system has shown the implementation method shown in Figure 4 to be inadequate while the cruise control is disengaged. The time required for the Arduino to read and then write the signal it receives from the throttle leads to unresponsive manual speed control while the cruise control is disengaged. A fix to this issue is proposed in section 5.5 of this blog post.

4.0 Software

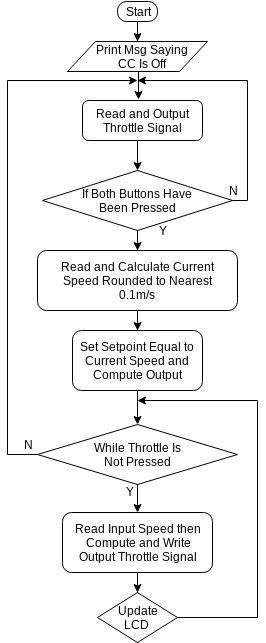

The cruise control system software was written in C using the Arduino IDE. Based on user inputs from two momentary pushbuttons, the software decides whether or not to pass the throttle signal as an output or compute a throttle output based on the PID controller. The software also updates the user on the current status of the system via an LCD and logs diagnostic information to an SD card.

Figure 5, below, shows a high level view of the logic flow of the code.

Figure 5. Basic logic flowchart of the cruise control software.

Source code, and more details about it, can be found on the Laboratorium’s Github repository found here.

4.1 Code Libraries

The continuous time PID controller derived in part one of this blog post series was digitized on the Arduino Nano using Brett Beauregard’s PID_v1 library (found here). This library was developed by Brett to implement continuous time PID controllers on Arduino microcontrollers.

Brett’s library was chosen to implement the PID controller because of its many robust features such as Derivative Kick and Initialization. Additionally, this library contains fantastic documentation which can be found here.

To avoid slowing the code’s main loop, interrupts were used to manage the change in setpoint brought on by a press of the speed increment decrement buttons. Using interrupts free’s up the Arduino’s processor from having to check whether or not there’s been a button press on every loop iteration. Instead, the processor reacts to pin changes and interrupts the execution of the main code to perform the function tied to the interrupt pin. However, the Arduino Nano only has a limited number of pins that can be used as interrupts. A library, written by GreyGnome (found here), enables the use of interrupts on any pin of the Arduino Nano. This library was used to free up pin real estate for the many components that are wired up to the Arduino.

5.0 Hardware Hook Up and Design

5.1 Instrumented Ebike Platform

Jason Moore, the lab’s PI, originally began constructing the instrumented ebike platform in 2009 from a large Surly single speed off road steel frame bicycle converted to an ebike with a conversion kit sold by Amped Bikes. The Amped Bikes kit consists of a brushless direct drive hub motor driven by a motor controller and powered by a 36V Li ion battery. More information on the build and the bike’s instrumentation system can be found in Jason’s dissertation found here.

Figure 6. The instrumented ebike today.

5.2 Electrical Hook Up

The electrical components of the control system revolve around an Arduino Nano which is the central processor for the hardware and logic of the cruise control system. Table 1, below, shows a complete list of the hardware used in this build.

| Component Name | Details | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Arduino Nano | ATmega328P Processor | Main Processor |

| Wheel Speed Sensor | DC generator in contact with rear tire (Click here for more information) | Control Loop Input |

| Voltage Divider | Used to step down wheel speed sensor voltage to a range measurable by the Arduino | Wheel Speed Sensor Signal Conditioning |

| Pushbuttons | Momentary pushbuttons to get user input | User Input |

| Battery | 7.2V NiCd | System Power |

| LCD | 16x2 character LCD | User Feedback |

| Motor Controller | Amped Bikes motor controller | Control Loop Output |

| SD Card Module | SPI SD card module for Arduino | Data Logging |

The Arduino Nano and the voltage divider circuits were soldered to a small 3" x 1" piece of protoboard. Wires (22 AWG) were soldered to the protoboard to connect the external components to the Nano. Figure 7 shows the completed Arduino board.

Figure 7. The Arduino board with wires attached.

With many of the components located on the handlebars, a majority of these wires were routed together along the top tube, up the head tube and stretched across to the handlebars. This task was facilitated using spiral wound cable housings, zip ties, and a 15 pin Molex connector. Once on the handlebars, wires were connected to header pins on the LCD and pushbuttons with Dupont connectors.

T-tap wire splices were used to cleanly splice power signals from the NiCd battery above the Arduino near the top tube and from the wheel speed sensor near the bottom bracket.

A complete wiring schematic of the cruise control system can be found on the laboratorium’s github here.

5.3 Electronics Housings

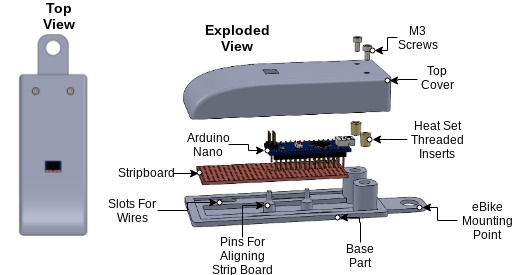

Housings for the Arduino Nano, pushbuttons and LCD were designed and 3D printed to enclose the electrical components and mount them to the ebike. Figure 8 shows the CAD model design of the Arduino housing. The housing’s design includes pins for press fitting the Arduino stripboard to the mount. Slots on the sides and top of the housing allow for wires to exit towards their destinations on the ebike. Threaded inserts on the base are used to secure the top cover using M3 screws.

Figure 8. Arduino housing design.

The Arduino housing is clamped to the downtube of the ebike by a socket head screw as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Arduino housing mounting point.

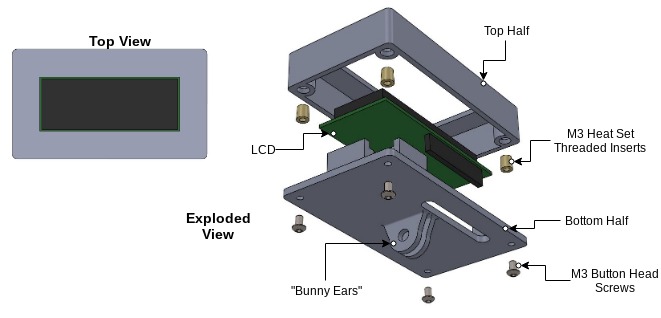

Both the LCD and button housings were 3D printed and designed to mount to the handlebars using a clamshell style mount used for securing GoPro cameras to bikes. Each mount had a pair of “bunny ears" designed to interface with the GoPro style mount. The LCD housing, shown in Figure 10 below, is a simple rectangular two-piece enclosure joined by button head screws.

Figure 10. LCD housing design.

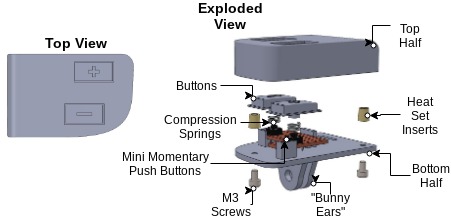

Similar to the LCD housing, the button housing is a two-piece, enclosure joined by screws. Inside the housing is a small piece of protoboard that the pushbuttons are soldered to. To make pressing the mini momentary pushbuttons more convenient for the user, larger button parts were 3D printed and offset from each mini momentary pushbutton using a compression spring as shown in Figure 11 below.

Figure 11. Button housing design.

As shown in Figure 12, the button housing is mounted on the right side of the handlebars near the throttle and brake lever for convenient access.

Figure 12. Button housing position on the handlebars.

5.4 Dead Man’s Switch

For safety reasons, a dead man’s switch was added to the cruise control system. The dead man’s switch works by cutting power from the Li+ battery through a mechanical relay. The relay’s coil is connected to a power circuit having a Reed switch. The Reed switch is actuated by a magnet strapped to the rider’s ankle. If the rider were to remove their ankle from the foot peg, separating the ankle magnet from the Reed switch, power to relay’s coil would be interrupted, opening the Li+ battery circuit. Sheet five of the master electrical schematic shows how the switch is wired up to the ebike’s powertrain.

5.5 Throttle Relay (Planned)

Currently, when cruise control is disengaged, the time it takes the Arduino to read the throttle signal and then write it to the motor controller is leading to a jerky ride. This is likely due to the intermittency in the throttle signal output to the motor controller produced by the delay in reading and writing the throttle signal through the Arduino. Placing a relay in line with the throttle signal will provide a continuous signal flow to the motor controller by eliminating the need to read and then write that signal when it passes through the Arduino. A continuous signal flow will eliminate the intermittency issues that make the bike feel jerky when the cruise control is disengaged.

Current plans for the relay have it placed inline with the throttle signal wire and switched by the Arduino through its digital write function. The proposed changes to the wiring schematic and software can be found on the project’s Github repository under the “relay” branch. Plans for the physical implementation of the relay include placing the relay on a piece of protoboard mounted to the bike’s top tube,inside the upper head tube triangle.

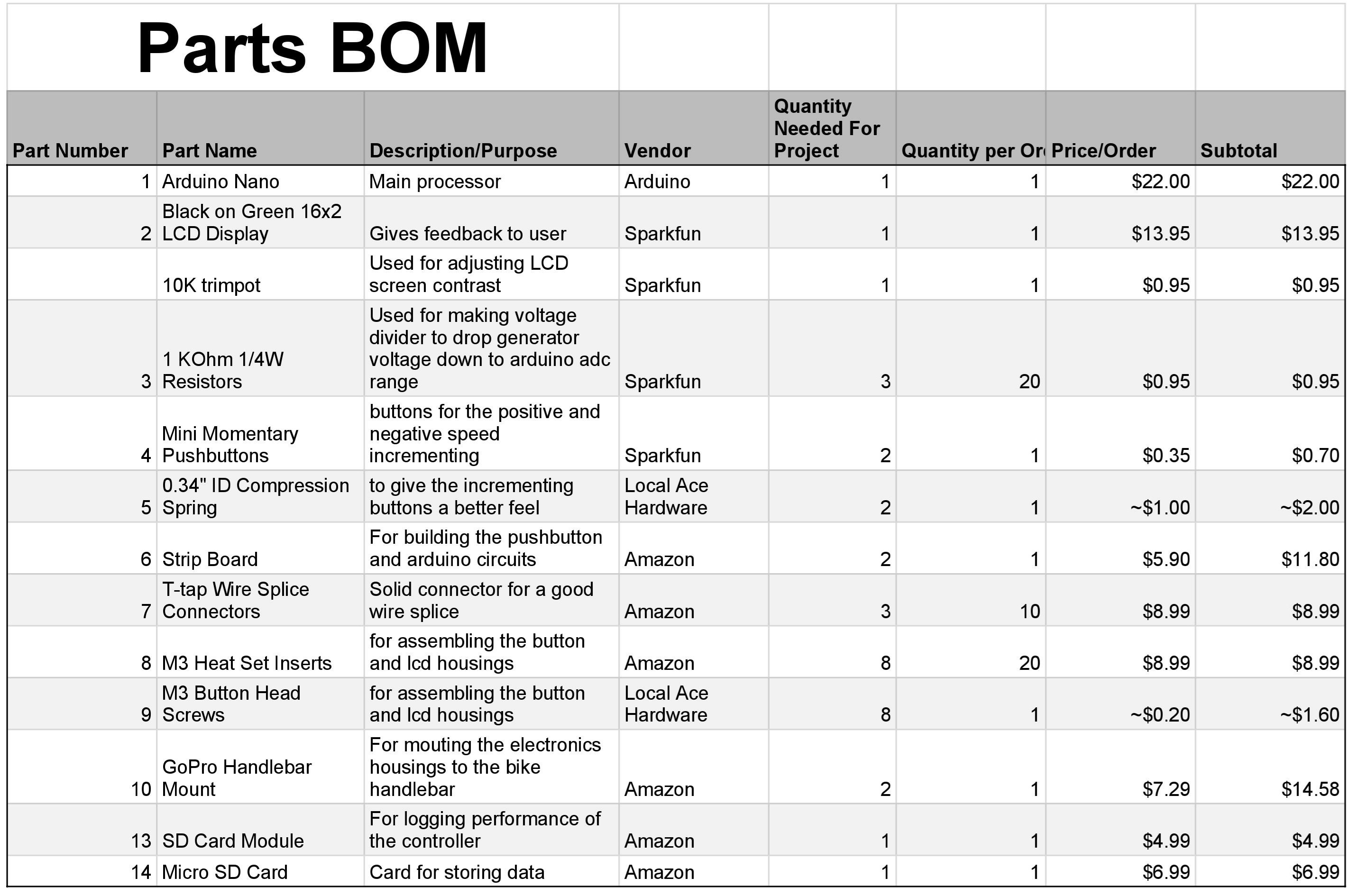

6.0 Bill of Materials

Table 2. Bill of materials (BOM) showing each part of project, where it was purchased, what quantity was purchased and its cost.

7.0 Suggested Improvements

Throughout the implementation of this design, I've made note of some improvements to the system's hardware design that could be made to address known issues. I have listed these below:

- Use a display that communicates via the SPI protocol to reduce the number of wires used

- For the Arduino board, use a custom PCB and connectors to increase the robustness of the board

- Implement a throttle relay (See section 5.5)

Here are some avenues for improving the accuracy and precision of the cruise control:

- Set a faster sampling time in the PID Arduino library

- Replace DC generator wheel speed sensor with a rotary encoder for smoother speed input (and preservation of the rear tire)

- Experiment with manual PID parameter tuning during outdoor testing to improve output surging while cruise control is engaged

8.0 Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nicholas Chan for writing the camera gimbal software that my speed control software is based off of. I’d also like to thank Brett Beuaregard for writing the PID library and it’s excellent documentation that is the heart of the speed control software. Finally, I’d like to thank Jason Moore for his support and mentorship throughout this project.